The Other US Ceiling: Shipping Bottlenecks and Logistic Logjams Hurting Economic Growth

Unless you have been living under a rock, you may have heard that the US is scheduled to run out of money on or around October 18th.

This approaching cliff has been both very predictable and very tiresome.

It means that, at some point in the next few weeks, the US government has to come together before that date to raise the debt ceiling and save the US from a technical default. If interested, you can find more here.

This is entirely a self-created "crisis" and therefore something that should never happen. The time to raise the debt ceiling was during one of the large legislative packages passed this winter rather than saving and using this deadline to raise the stakes of current policy debates.

We thought rather than add our voices to the endless (and tiring) debt ceiling coverage we would instead focus on a different and yet equally important "ceiling" in the US.

In this case, the role of "transitory" supply chain crunches acting as a "ceiling" on US economic growth.

In our case, we want to explore the role of "transitory" supply chain issues acting as:

a limiting factor on the pandemic economic recovery,

crimping growth and

chewing up some of potential productivity advances with higher prices acting as a hidden taxon American consumers and companies.

We wrote about these in one of the first issues of Pebble back in the summer and worried that they might not be so transitory at all. Fast forward four months and the problems only seem to be worsening. We last gave an example of one potential issue when we analyzed the challenge of getting sneakers onto American feet and why it might be better to do your back to school shopping early.

Care to find out more? We have posted 4 charts on our blog here.

These days we are not the only ones discussing it now:

At a congressional hearing Tuesday, Mr. Powell said that the burst of inflation this year has been broader and more persistent than anticipated because supply chains remain snarled.

Let's dive in as to why:

Exhibit A: Shipping rates.

Already extremely elevated and continuing to rise.

This is happening partially because of snarls, Covid-19 delays and issues at the world's most important ports.

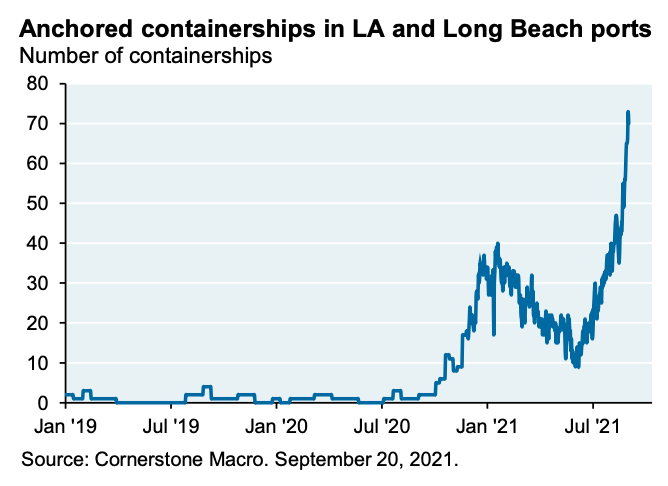

Exhibit B: Number of ships waiting at anchor at the main US West Coast ports.

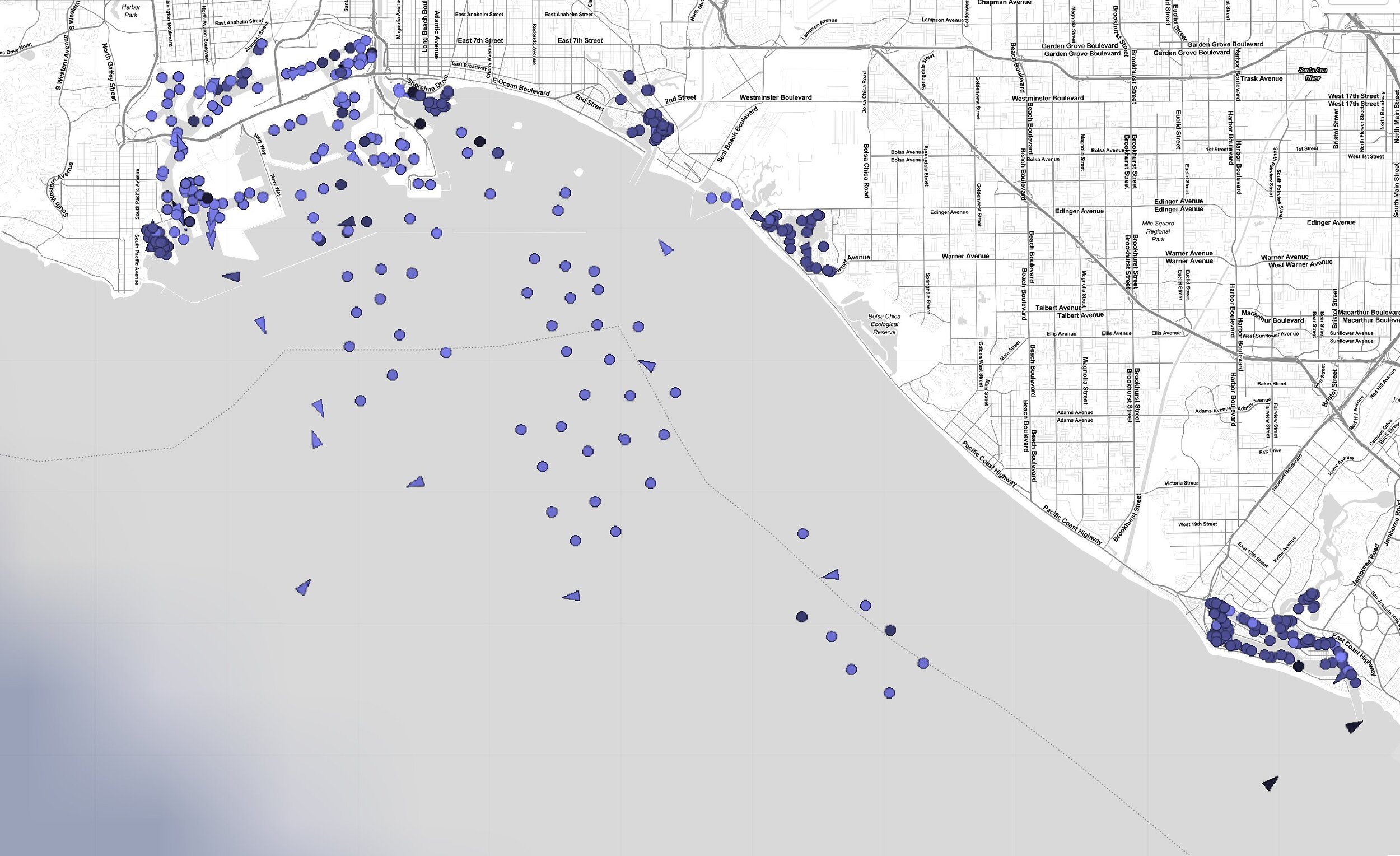

Here is what this looks like on the ground. Each dot is a ship waiting to be unloaded in LA or Long Beach:

Exhibit C: Unsurprisingly, this is feeding into manufacturing delivery times which are rising painfully.

Where does this leave us?

Nowhere good!

Disrupted supply chains.

High transportation costs.

Longer manufacturing times.

Large gaps between factory orders and output.

And we have not even gotten to the labor scarcity that is forcing companies large and small to operate below capacity and with wage pressures.

This is what struck us about the inflation debate last winter and spring. Rather than a few one-off imbalances between supply and demand there were instead a myriad of short term forces combining with structural long term shifts to produce something far more problematic.

We are obviously not experts in supply chain logistics or global shipping patterns but we can follow those who are. And they have been alarmed for months. When many of the economists and policymakers are insisting that inflationary pressures will be transitory but their counterparts in ports and shipping and supply chain management are saying that issues like semiconductor shortages (or shipping problems) could last for years we tend to believe them.

Add it all up and it suggests slower growth and higher inflation. So, good for lower growth sectors like Utilities and Tech and also good for those sectors that benefit from higher commodity prices.

Here is a final chart to underline this theme.

J.D. Power expects U.S. automakers to sell just over 1 million vehicles in September, for an annual sales rate of 12.2 million. That’s a rate that’s 4 million lower than last year, and 4.9 million below September of 2019.

So, we are missing out on 3-400K auto sales a month not because of a lack of demand but rather a lack of supply. This adds up and also reinforces why is it so important that Ford and GM are investing in new capacity to change this.

*******

Have questions? Care to find out more? Feel free to reach out at contact@pebble.finance or join our Slack community to meet more like-minded individuals and see what we are talking about today. All are welcome.